Tir de Fona Internacionale- 7th International Slinging Competition in Mallorca 2020.

March 7, 2020 by admin

Filed under Onra, Special Forces

Held the same weekend as The Heritage Cup in Guam last weeekend– Here is A quick video of the 7th International Slinging Competition in Mallorca 2020. The videos and photos used here have been collected together from a variety of sources

The Heritage Cup 2020

March 1, 2020 by admin

Filed under Special Forces

Early-day Spanish explorers have at several times documented stone slinging competitions built within village gatherings in Guam. Since 2017, local stone slingers gathered throughout the island have brought it back.

For this first segment of our 3 event series– From February 29th til March 2nd, ACHO Marianas in conjunction with the Guam History & Chamorro Heritage Day Festival will be hosting slingers from the CNMI for a 3 day event to commemorate the Mariana Islands most distinguished weapon and tool–the Sling and sling-stone.

HU NONI HAO GUAHAN: Para i Onra

March 1, 2020 by admin

Filed under Special Forces

Stone slinging is an indigenous martial art with the ancestors of the Mariana Islands. Long suffocated with the Spanish colonization almost 500 years ago–Sling-stone artifacts are still found or “received”. Buried in the ground, underwater, or sonetimes even in plain sight above surface–Sling-stone gifts have been digested as a calling for stone slinging to once again protect and defend our people.

HITA TALKS: Guam Slinging Conversation

February 13, 2020 by admin

Filed under Special Forces

Shortly after a performance at the Tir de Fona Internacionale, members of Acho Marianas Guam engage in The University of Guam’s HITA TALKS with Carlos Madrid of the Micronesian Area Reseach Center for a conversation through the past, present, and future of Guam Slinging and its role int he 500 year anniversary and commemoration of Guams first Encounter with European explorers in 1521.

House of TAGA Tinian TANK. In Store & Online

February 12, 2020 by admin

Filed under Special Forces

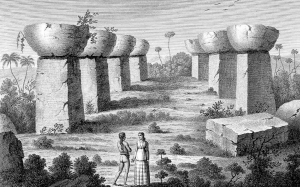

Houses of the Ancients

Latte structures are stone archaeological remains unique to the Mariana Islands. A stone pillar supports a hemispherical capstone to form a latte. The ancient CHamorus generally arranged latte in two parallel rows of four or more pairs to support their important rectangular, steep pitched roof, pole and thatch buildings. Communities in coastal areas, river valleys, and a few upland areas, seem to have competed to build larger and larger latte structures. The Spanish missionaries referred to the latte as casa de los antigos or houses of the ancients. Latte have become a significant icon in contemporary Mariana Islands architecture and serve as a symbol of the CHamoru people and their proud past.

Ancient CHamorus used latte as a foundation for wooden with thatch roof structures. Several archaeologists disagree on the date of the earliest latte. Some say that CHamorus built latte as early as B.P. 1200, others think it was not until B.P. 800, but these experts generally agree that CHamorus stopped building traditional latte houses by B.P. 300.

CHamorus inhabited Guam and the Mariana Islands at least 2,800 years before they constructed latte. Many experts regard latte and the cultural complex of tools and pottery associated with them as a natural development of CHamoruo culture. Nevertheless, some are convinced that latte were the work of a conquering people who invaded the Marianas or perhaps another wave of migration.

Handcrafted:

May 17, 2019 by admin

Filed under Special Forces

Not many people know this, but most of Fokai;s Bali made products are handcrafted. Very slight occasional size differences are only as inevitable as human error. Heres a quickview of a piece of the process before the final touches

INTERSCHOILASTIC SLINGING via KUAM

April 30, 2019 by admin

Filed under Special Forces

News

10 schools compete in sling event

Tuesday, April 30th 2019, 1:58 PM ChST

By Dave Delgado

Image

10 schools were represented at the first of many sling competitions to hopefully be part of GDOE and their Chamorro activities. The slinging went down at the Tiyan Softball Field with targets set up at different distances for elementary, middle and high school participants.

Tony Diaz, the Event Organizer, said, “They’re here because they believe in this sport and they want to participate and they are having a blast as you can see. It’s really a pleasure to see them walk in the footsteps of our ancestors.”

For safety issues, Diaz created stones that were suitable for the young competitors to use. They were replicas of what our ancestors used. “They are actually made out of silicone and corn starch. We shaped them into the sling stones that we know that our ancestors used. It’s a safety issue and we certainly can’t use stones here because we have students and kids. So for safety reasons we went ahead and used that type of projectile,” he said.

The slings used for the competition were made out of paracord and done by students and faculty from the various schools.

Diaz added, “There are certain variations and certain types of materials that they are using. Mainly paracord and other types of strings like fiber and strings like twine maybe and some have probably have gone as far as the Pago bark fiber that they make their strings with.”

Diaz says the long term goal is to one day have slinging in the Micronesian Games and to also open up the sport to all ages.

“We would like to also see this also become an interscholastic sport, kind of what we do with volleyball, basketball and things in that nature in those sports. This is our sport this is our culture and this is what we know our ancestors did. It is also in the history books. The kids are really having a blast and they like this sport and I think it’s enough to make it a sport as far as I’m concerned,” he said.

What is a sling?

February 23, 2019 by admin

Filed under Special Forces

What is a sling?

What is a sling?

The sling was likely mankind’s first, true projectile weapon. It generally consists of two cords and a pouch. These cords are held in one hand and a projectile is placed in the pouch. The length of the sling provides greater mechanical advantage than one’s arms. Projectiles can be slung over 1500 feet (450m) at speeds exceeding 250 miles per hour (400 kph). The sling is unique in that the movement of the weapon is merely an extension of the user’s body. The power and accuracy of the weapon is not by technological means, but rather user skill. The connection between slinger and sling is an intimate one.

There are many historical sources which describe the sling’s extraordinary performance characteristics. Its main competitor, the bow, had both a shorter range and slower rate of fire. Additionally, dozens of historical sources note the remarkable accuracy of a sling in trained hands. Although use of the weapon diminished after the fall of the Roman Empire, the weapon’s supremacy as the premier, personal, long-range weapon was not supplanted until the 15th century. Ultimately, changes in society, technology and military tactics rendered the sling ineffective in large-scale, organized warfare. The sling continues to be used in various smaller conflicts and by enthusiasts to this day.

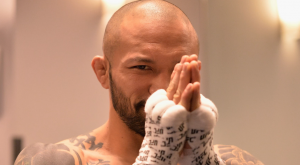

Kid Yamamoto: a Hero’s Hero. RIP KID!

September 23, 2018 by admin

Filed under Special Forces

Japanese legend Norifumi Yamamoto, the one-time pound-for-pound king, passed away this week from cancer.

The bafflingly named Hero’s was launched in 2005 as an offshoot of the great kickboxing promotion, K-1. An ultra successful crossover event with PRIDE FC in 2002 had left the K-1 big wigs thinking that they had better start working their way into this mixed martial arts malarkey and so Hero’s became K-1’s MMA arm.

Revisiting the run of Hero’s events it is strange to realize that the company was only around for a couple of years—from March 2005 until December 2007. DREAM lasted longer, PRIDE had been going for almost a decade when Hero’s started up and ended the same year, and even the youngest Japanese promotion, Rizin, has outlasted Hero’s at this point. Yet in those three years, Hero’s gave us some of the more memorable moments in Japanese MMA.

Kazushi Sakuraba abandoned PRIDE—the house that he had built—in order to join Hero’s, returning from the brink of defeat against Kestutis Smirnovas and losing in one of the sketchiest bouts of all time to a greased up Yoshihiro Akiyama. Genki Sudo found a home in Hero’s and was able to employ more and more theater in his legendary entrances to the point that he eventually abandoned fighting altogether and formed a successful pop group. Theater and narratives are a large part of fighting, but in terms of raw talent there was one man who stood out from the herd in Hero’s and whose highlight reels could be pulled up on YouTube at any point to convince friends that there was a future to this MMA thing: Norifumi “Kid” Yamamoto.

A Bolt from the Blue

By the time that Hero’s announced its first grand prix, Yamamoto had already established something of a reputation as Japanese MMA’s bad boy—hitting opponents late after having knocked them out and living a dramatic life outside of the ring. He had dabbled in kickboxing in 2004 with a victory over Takehiro Murahama and a surprisingly competitive and dramatic fight with the great Masato on New Year’s Eve. But as far as MMA went, there was an awful lot of hype and fans just weren’t sure they had seen enough to justify it yet.

Yamamoto had competed successfully in Shooto but had never won a Shooto title—pretty much a rite of passage for a Japanese MMA prospect. Scouted by K-1, Yamamoto found himself in a similar position to Tenshin Nasukawa’s modern position in Rizin—the company liked him but weren’t finding him suitable opponents or building a division for him to compete in. Yamamoto went from fighting the formidable Jeff Curran (16-5-1) in Icon Sport in May of 2003 to taking three fights against opponents with no MMA record in K-1 through to 2005.

Kid was a potential star, but fighting nobodies wasn’t going to get him anywhere and he knew this. So when Hero’s announced their middleweight grand prix, Yamamoto decided to take a crack at Hero’s’s first belt. Hero’s followed the Japanese tradition of making up its own weightclasses that deliberately didn’t conform with anyone else’s, so middleweight was in fact 75 kilograms or 165 pounds. This meant that Hero’s could enlist the services of the excellent lightweights Genki Sudo and Caol Uno to legitimize their first tournament. The tournament would have been even better had Joachim Hansen not been poached by PRIDE just before it began. Kid Yamamoto, however, was not a respected lightweight—he was a bantamweight at best who floated up to featherweight to get fights.

As far as ballsy moves go, Yamamoto’s decision to enter the Hero’s middleweight grand prix was one of the ballsiest in MMA. Though he was 5’4″ on a good day, the tournament quickly stopped being about Yamamoto being undersized and became about the rest of the fighters being underpowered.

The Yamamoto clan are now a wrestling dynasty: the father, Ikuei Yamamoto had competed in the Munich Olympics, the elder sister Miyuu is a three time world champion, and Norifumi’s younger sister, Seiko is a four time world champion who achieved a bronze in the ADCC no gi grappling world championships eleven years after her last world title in wrestling. While Norifumi missed out on a serious wrestling career, he was able to put his talent to use in learning the MMA game and also entered The Contenders, a grappling tournament wherein he bested judo submissions wizard Koji Komuro. Throughout the 2005 grand prix, fans were treated to numerous instances of Yamamoto throwing around larger opponents in styles that didn’t always make sense to the eyes. The sight of Yamamoto holding Royler Gracie’s toes about an inch off the floor in a standing guillotine will always be hilarious.

We can never pretend that Yamamoto was a striking savant—his game was the leaping right hook and some hard kicks and that was about it. But what Yamamoto did have was ridiculous speed. Almost everyone he fought would inevitably try to kick or knee him in the head and he would return with his right hook—often wound up from far behind him—before they could get their foot back to the ground.

On the first night of the Hero’s grand prix, Yamamoto knocked Royler Gracie stiff with a right hook to the jaw, then took on Japanese MMA legend Caol Uno in the second round, forcing a TKO due to cuts over Uno’s left eye from stiff right straights and hooks. Genki Sudo had worked through his half of the bracket, submitting Kazuyuki Miyata and Hiroyuki Takaya and this set up a Yamamoto-Sudo final at K-1 Premium Dynamite 2005. The bout headlined K-1’s year-ending show at the Osaka Dome on a card containing kickboxing legends like Ernesto Hoost and Semmy Schilt. After a very tentative few minutes, Yamamoto finally caught the grappling savant with a right hook as he came in and sent him to the mat. Flurrying for the finish, Yamamoto’s finest moment was somewhat undercut by a premature stoppage. Yet the accomplishment has never been replicated: a fighter going up two weightclasses to run through a tournament with two fights in one night, stopping each opponent.

Yamamoto’s career peaked with his victory in the 2005 grand prix, but injuries and strange matchmaking left us with a great many unanswered questions. There was occasional talk about a possible match up between Yamamoto and PRIDE’s lightweight king, Takanori Gomi. Others wanted to see Yamamoto in with Urijah Faber, a trailblazer in the featherweight class in the United States. But while those match ups were complicated by the fighters being under different promotions, Hero’s did a bad job of finding Yamamoto opponents even under the same banner. The Genki Sudo rematch never happened and Sudo retired in 2007, but perhaps more surprisingly Gesias ‘JZ’ Cavalcante won the two subsequent Hero’s tournaments in Yamamoto’s division and that eagerly anticipated fight never materialized. Yamamoto had proven that he was the star and after starching Kazuyuki Miyata with the finest and quickest flying knee ever to grace MMA, Yamamoto wanted to return to his natural weight class.

Try to take note of where Yamamoto’s right foot last touches the mat before the knee, and then where it lands afterwards. There are some who attest that Yamamoto might have been the greatest raw athlete to ever compete in MMA. Watching Yamamoto hammer the heavy bag is one of the more impressive sights this writer has seen in the gym.

Hero’s best efforts were pretty bad. At featherweight, Yamamoto was matched against the 0-0-0 wrestler, Istvan Majoros in a fight so lopsided that he felt bad about punching the guy.

Another interesting quirk of Yamamoto’s game, he was a murderer with knees to the body out of the double collar tie, even against much taller opponents like Caol Uno.

Then on the same night that JZ Cavalcante won the 2007 grand prix, Yamamoto fought the 1-1 Bibiano Fernandes in the co-main event—his first fight at bantamweight. Fernandes went on to become something very special indeed over the coming years, but it was a truly weird piece of matchmaking at the time.

The last great showing Yamamoto had came against the formidable Rani Yahya on the last night of 2009. Yahya then had a 12-3 MMA record, had won gold at ADCC earlier in the year, and was fresh off a decision loss to Chase Beebe for the WEC bantamweight championship. Yamamoto, looking more polished and thoughtful, set to work with hard kicks and counter punches. He dug body shots with his left hand and dipped out after his right hooks. It was one of Yamamoto’s smoothest performances in the ring, and he handed Yahya his first knockout loss in the second round.

A surprisingly smooth and measured Yamamoto.

Then Yamamoto injured his knee and was out for two years. The Kid of old never came back. He fought Joe Warren in the opening round of the DREAM featherweight grand prix (back up a weight class) on his return in 2009 but lost a split decision to the American wrestler. A decision loss to the unremarkable Masanori Kanehara followed wherein Yamamoto was dropped on his face. His feet were so much slower and it was becoming clear that his chin was not up to it any more. In almost all of his remaining fights Yamamoto’s chin looked shaky and he just didn’t seem to have that electricity that made him impossible to look away from in 2005. In a passing of the torch moment, Yamamoto—MMA’s most notorious little man—met Demetrious Johnson in February 2011 and was handily outworked. The men Yamamoto was struggling against by the very end of his career likely wouldn’t have laid a glove on him at his best, but that is the nature of fighting.

In truth, to many fans Yamamoto remains a case of untested potential similar to the late Kevin Randleman but with a far more successful run in the fights he did have. But even as his abilities waned, Kid Yamamoto impacted the future of Japanese MMA even as it was entering a sleepy, post-PRIDE hibernation. Yamamoto had built his own gym to train on his own terms and as his own career wound down, successful youngsters began to trickle out of the small Yamamoto Sports Academy: the respectable Issei Tamura, the wily Kotetsu Boku, and the hot young prospect Yusuke Yachi to name a few. Kyoji Horiguchi was a quiet gym rat at the YSA through his teens, often found behind the front desk or teaching the kids wrestling classes, and now he is the best fighter Japan has perhaps ever produced. If you have any doubt of Yamamoto’s direct influence on Horiguchi, watch Horiguchi’s Shooto run wherein he looks the spitting image of Kid, leaping in behind lead hooks over and over again. Even years before Horiguchi began competing, Killer Bee gym (as it was in its previous incarnation) was the training grounds of the fearsome Akira Kikuchi—often regarded as one of the big “what ifs” of Japanese MMA. Yamamoto’s elder sister Miyuu and her son—Kid’s nephew, Erson, also fight out of the YSA. Rizin undoubtedly has a lot to thank Norifumi Yamamoto for, even if he never fought under their banner.

As he became more of an occasional competitor, Yamamoto also continued to explore his love of art and tattoos, coming into each bout more beautifully decorated than the last, with stunning shorts to match. In a sport full of atrocious ink with almost half of the fighters you see having their own name tattooed across their back lest they forget, Yamamoto’s ink stood out as genuine art. Strangely enough Yamamoto also began working on a curry restaurant in his semi-retirement, hilariously named Curry Shower, but just as the Kid was starting his second act he was cut down by cancer.

For the past few years, we have all been writing about Kid Yamamoto as an old man because in the fight game he was. One of the guilty pleasures of any fight writer is cracking wise about “old timers” and then being forced to eat crow if they can turn back the clock for one night. That’s the way it is supposed to be: 40-year-old men aren’t supposed to be able to keep up with 25-year-old kids. The heartbreaking thing is that in any other way of looking at it, in any other aspect of life, Kid Yamamoto was not an old man. He wasn’t even middle aged. The name ‘Kid’ had started to seem silly by the time Yamamoto hit 30, but to Miyuu Yamamoto he was still just her little brother, and to Ikuei Yamamoto, I’m sure Norifumi was still his baby boy.

Sling (weapon) from Wikipedia

September 18, 2018 by admin

Filed under Special Forces

Home-made sling

Home-made sling

A sling is a projectile weapon typically used to throw a blunt projectile such as a stone, clay, or lead “sling-bullet”. It is also known as the shepherd’s sling. Someone who specialises in using slings is called a slinger.

A sling has a small cradle or pouch in the middle of two lengths of cord. The sling stone is placed in the pouch. The middle finger or thumb is placed through a loop on the end of one cord, and a tab at the end of the other cord is placed between the thumb and forefinger. The sling is swung in an arc, and the tab released at a precise moment. This frees the projectile to fly to the target. The sling essentially works by extending the length of a human arm, thus allowing stones to be thrown much farther than they could be by hand.

The sling is inexpensive and easy to build. It has historically been used for hunting game and in combat. Film exists of Spanish Civil War combatants using slings to throw grenades over buildings into enemy positions on the opposite street. Today the sling is of interest as a wilderness survival tool and an improvised weapon.[1]

The sling in antiquity

Origins

The sling is an ancient weapon known to Neolithic peoples around the Mediterranean, but is likely much older. It is possible that the sling was invented during the Upper Paleolithic at a time when new technologies such as the spear-thrower and the bow and arrow were emerging.

With the exception of Australia, where spear throwing technology such as the woomera predominated, the sling became common all over the world, although it is not clear whether this occurred because of cultural diffusion or as an independent invention.

Archaeology

Whereas sling-bullets are common finds in the archaeological record, slings themselves are rare. This is both because a sling’s materials are biodegradable and because slings were lower-status weapons, rarely preserved in a wealthy person’s grave.

The oldest-known surviving slings—radiocarbon dated to ca. 2500 BC—were recovered from South American archaeological sites located on the coast of Peru. The oldest-known surviving North American sling—radiocarbon dated to ca. 1200 BC—was recovered from Lovelock Cave, Nevada.[2]

The oldest known extant slings from the Old World were found in the tomb of Tutankhamen, who died about 1325 BC. A pair of finely plaited slings were found with other weapons. The sling was probably intended for the departed pharaoh to use for hunting game.[3]

Another Egyptian sling was excavated in El-Lahun in Al Fayyum Egypt in 1914 by William Matthew Flinders Petrie, and now resides in the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology—Petrie dated it to about 800 BC. It was found alongside an iron spearhead. The remains are broken into three sections. Although fragile, the construction is clear: it is made of bast fibre (almost certainly flax) twine; the cords are braided in a 10-strand elliptical sennit and the cradle seems to have been woven from the same lengths of twine used to form the cords.[4]

Slingers on Trajan’s Column.

Ancient representations

Representations of slingers can be found on artifacts from all over the ancient world, including Assyrian and Egyptian reliefs, the columns of Trajan[5] and Marcus Aurelius, on coins and on the Bayeux Tapestry.

The oldest representation of a slinger in art may be from Çatalhöyük, from approximately 7,000 BC, though it is the only such depiction at the site, despite numerous depictions of archers.[6]

Written history

Ancient Greek lead sling bullets with a winged thunderbolt molded on one side and the inscription “?????” (Dexai) meaning “take that” or “catch” on the other side, 4th century BC, from Athens, British Museum.[7]

The sling is mentioned by Homer[8] and by other Greek authors. Xenophon in his history of the retreat of the Ten Thousand, 401 BC, relates that the Greeks suffered severely from the slingers in the army of Artaxerxes II of Persia, while they themselves had neither cavalry nor slingers, and were unable to reach the enemy with their arrows and javelins. This deficiency was rectified when a company of 200 Rhodians, who understood the use of leaden sling-bullets, was formed. They were able, says Xenophon, to project their missiles twice as far as the Persian slingers, who used large stones.[9]

Ancient authors seemed to believe, incorrectly, that sling-bullets could penetrate armour, and that lead projectiles, heated by their passage through the air, would melt in flight.[10][11] In the first instance, it seems likely that the authors were indicating that slings could cause injury through armour by a percussive effect rather than by penetration. In the latter case we may imagine that they were impressed by the degree of deformation suffered by lead sling-bullet after hitting a hard target.[12]

Various ancient peoples enjoyed a reputation for skill with the sling. Thucydides mentions the Acarnanians and Livy refers to the inhabitants of three Greek cities on the northern coast of the Peloponnesus as expert slingers. Livy also mentions the most famous of ancient skillful slingers: the people of the Balearic Islands. Of these people Strabo writes: And their training in the use of slings used to be such, from childhood up, that they would not so much as give bread to their children unless they first hit it with the sling.[13]

The late Roman writer Vegetius, in his work De Re Militari, wrote:

- Recruits are to be taught the art of throwing stones both with the hand and sling. The inhabitants of the Balearic Islands are said to have been the inventors of slings, and to have managed them with surprising dexterity, owing to the manner of bringing up their children. The children were not allowed to have their food by their mothers till they had first struck it with their sling. Soldiers, notwithstanding their defensive armour, are often more annoyed by the round stones from the sling than by all the arrows of the enemy. Stones kill without mangling the body, and the contusion is mortal without loss of blood. It is universally known the ancients employed slingers in all their engagements. There is the greater reason for instructing all troops, without exception, in this exercise, as the sling cannot be reckoned any encumbrance, and often is of the greatest service, especially when they are obliged to engage in stony places, to defend a mountain or an eminence, or to repulse an enemy at the attack of a castle or city.[14]

According to description of Procopius, the sling had an effective range further than a Hun bow and arrow. In his book Wars of Justinian, he recorded the felling of a Hun warrior by a slinger:

- Now one of the Huns who was fighting before the others was making more trouble for the Romans than all the rest. And some rustic made a good shot and hit him on the right knee with a sling, and he immediately fell headlong from his horse to the ground, which thing heartened the Romans still more[15]

Biblical accounts

The sling is mentioned in the Bible, which provides what is believed to be the oldest textual reference to a sling in the Book of Judges, 20:16. This text was thought to have been written about 6th century BC,[16] but refers to events several centuries earlier.

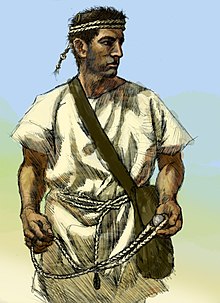

The Bible provides a famous slinger account, the battle between David and Goliath from the First Book of Samuel 17:34-36, probably written in the 7th or 6th century BC, describing events having occurred around the 10th century BC. The sling, easily produced, was the weapon of choice for shepherds fending off animals. Due to this, the sling was a commonly used weapon by the Israelite militia.[17] Goliath was a tall, well equipped and experienced warrior. In this account, the shepherd David convinces Saul to let him fight Goliath on behalf of the Israelites. Unarmoured and equipped only with a sling, 5 smooth rocks, and his staff; David defeats the champion Goliath with a well-aimed shot to the head.

Use of the sling is also mentioned in Second Kings 3:25, First Chronicles 12:2, and Second Chronicles 26:14 to further illustrate Israelite use.

An artistic depiction of a slinger from the Balearic islands, famous for the skill of its slingers.

Combat

Ancient peoples used the sling in combat—armies included both specialist slingers and regular soldiers equipped with slings. As a weapon, the sling had several advantages; a sling bullet lobbed in a high trajectory can achieve ranges in excess of 400 metres (1,300 ft).[18] Modern authorities vary widely in their estimates of the effective range of ancient weapons. A bow and arrow could also have been used to produce a long range arcing trajectory, but ancient writers repeatedly stress the sling’s advantage of range. The sling was light to carry and cheap to produce; ammunition in the form of stones was readily available and often to be found near the site of battle. The ranges the sling could achieve with molded lead sling-bullets was surpassed only by the strong composite bow.

Caches of sling ammunition have been found at the sites of Iron Age hill forts of Europe; some 22,000 sling stones were found at Maiden Castle, Dorset.[19] It is proposed that Iron Age hill forts of Europe were designed to maximise the effective defense of slingers.

The hilltop location of the wooden forts would have given the defending slingers the advantage of range over the attackers, and multiple concentric ramparts, each higher than the other, would allow a large number of men to create a hailstorm of stone. Consistent with this, it has been noted that defenses are generally narrow where the natural slope is steep, and wider where the slope is more gradual.

Construction

A classic sling is braided from non-elastic material. The traditional materials are flax, hemp or wool; those of the Balearic islanders were said to be made from a type of rush. Flax and hemp resist rotting, but wool is softer and more comfortable.

Braided cords are used in preference to twisted rope, as a braid resists twisting when stretched. This improves accuracy.[20]

The overall length of a sling can vary significantly; a slinger may have slings of different lengths, a longer sling being used when greater range is required. A length of about 61 to 100 cm (2.00 to 3.28 ft) would be typical.

At the centre of the sling, a cradle or pouch is constructed. This may be formed by making a wide braid from the same material as the cords or by inserting a piece of a different material such as leather. The cradle is typically diamond shaped (although some take the form of a net,) and will fold around the projectile in use. Some cradles have a hole or slit that allows the material to wrap around the projectile slightly, thereby holding it more securely.

At the end of one cord (called the retention cord) a finger-loop is formed.[citation needed] At the end of the other cord (the release cord,) it is a common practice to form a knot or a tab.[citation needed] The release cord will be held between finger and thumb to be released at just the right moment, and may have a complex braid to add bulk to the end. This makes the knot easier to hold, and the extra weight allows the loose end of a discharged sling to be recovered with a flick of the wrist.[citation needed]

Polyester is an excellent material for modern slings, because it does not rot or stretch and is soft and free of splinters.[citation needed]

Modern slings are begun by plaiting the cord for the finger loop in the center of a double-length set of cords.[citation needed] The cords are then folded to form the finger-loop. The cords are plaited as a single cord to the pocket. The pocket is then plaited, most simply as another pair of cords, or with flat braids or a woven net. The remainder of the sling is plaited as a single cord, and then finished with a knot. Braided construction resists stretching, and therefore produces an accurate sling.[citation needed]

Ammunition

Sling-bullets of baked clay and stone found at Ham Hill Iron Age hill fort.

The simplest projectile was a stone, preferably well-rounded. Suitable ammunition is frequently from a river. The size of the projectiles can vary dramatically, from pebbles massing no more than 50 grams (1.8 oz) to fist-sized stones massing 500 grams (18 oz) or more.

Projectiles could also be purpose-made from clay; this allowed a very high consistency of size and shape to aid range and accuracy. Many examples have been found in the archaeological record.

The best ammunition was cast from lead. Leaden sling-bullets were widely used in the Greek and Roman world. For a given mass, lead, being very dense, offers the minimum size and therefore minimum air resistance. In addition, leaden sling-bullets are small and difficult to see in flight.

In some cases, the lead would be cast in a simple open mould made by pushing a finger or thumb into sand and pouring molten metal into the hole. However, sling-bullets were more frequently cast in two part moulds. Such sling-bullets come in a number of shapes including an ellipsoidal form closely resembling an acorn – this could be the origin of the Latin word for a leaden sling-bullet: glandes plumbeae (literally leaden acorns) or simply glandes (meaning acorns, singular glans).

Other shapes include spherical and (by far the most common) biconical, which resembles the shape of the shell of an almond nut or a flattened American football.

The ancients do not seem to have taken advantage of the manufacturing process to produce consistent results; leaden sling-bullets vary significantly. The reason why the almond shape was favoured is not clear: it is possible that there is some aerodynamic advantage, but it seems equally likely that there is some more prosaic reason, such as the shape being easy to extract from a mould, or the fact that it will rest in a sling cradle with little danger of rolling out.

Almond shaped leaden sling-bullets were typically about 35 millimetres (1.4 in) long and about 20 millimetres (0.79 in) wide, massing approximately 28 grams (0.99 oz). Very often, symbols or writings were moulded into lead sling-bullets. Many examples have been found including a collection of about 80 sling-bullets from the siege of Perusia in Etruria from 41 BC, to be found in the museum of modern Perugia. Examples of symbols include a stylised lightning bolt, a snake, and a scorpion – reminders of how a sling might strike without warning. Writing might include the name of the owning military unit or commander or might be more imaginative: “Take this,” “Ouch,” and even “For Pompey’s backside” added insult to injury, whereas dexai (“take this” or “catch!”)[7] is merely sarcastic.

Julius Caesar writes in De bello Gallico, book 5, about clay shot being heated before slinging, so that it might set light to thatch.[21]

“Whistling” bullets[edit]

Some bullets have been found with holes drilled in them. It was thought the holes were to contain poison. John Reid of the Trimontium Trust, finding holed Roman bullets excavated at the Burnswark hillfort, has proposed that the holes would cause the bullets to “whistle” in flight and the sound would intimidate opponents. The holed bullets were generally small and thus not particularly dangerous. Several could fit into a pouch and a single slinger could produce a terrorizing barrage. Experiments with modern replicas demonstrate they produce a whooshing sound in flight. [22]

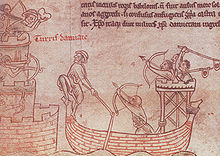

The sling in medieval period

Europe

The Bayeux Tapestry of the 1070s portrays the use of slings in a hunting context. Frederick I, Holy Roman Emperor employed slingers during the Siege of Tortona in 1155 to suppress the garrison while his own men built siege engines.[23] On the Iberian peninsula, the Spanish and Portuguese infantry favoured it against light and agile Moorish troops. The staff sling continued to be used in sieges and the sling was used as a part of large siege engines.[24]

The Americas

A South American sling made of alpaca hair

The sling was known throughout the Americas.[25]

In the ancient Andean civilizations such as Inca Empire, slings were made from llama wool. These slings typically have a cradle that is long and thin and features a relatively long slit. Andean slings were constructed from contrasting colours of wool; complex braids and fine workmanship can result in beautiful patterns. Ceremonial slings were also made; these were large, non-functional and generally lacked a slit. To this day, ceremonial slings are used in parts of the Andes as accessories in dances and in mock battles. They are also used by llama herders; the animals will move away from the sound of a stone landing. The stones are not slung to hit the animals, but to persuade them to move in the desired direction.

The sling was also used in the Americas for hunting and warfare. One notable use was in Incan resistance against the conquistadors. These slings were apparently very powerful; in 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus, historian Charles C. Mann quoted a conquistador as saying that an Incan sling “could break a sword in two pieces” and “kill a horse.”[26] Some slings spanned as much as 2.2 metres (86 in) long and weighed an impressive 410 grams (14.4 oz).[27][28]

Variants

Medieval traction trebuchet next to a staff slinger

Staff sling

The staff sling, also known as the stave sling, fustibalus (Latin), fustibale (French), consists of a staff (a length of wood) with a short sling at one end. One cord of the sling is firmly attached to the stave and the other end has a loop that can slide off and release the projectile. Staff slings are extremely powerful because the stave can be made as long as two meters, creating a powerful lever. Ancient art shows slingers holding staff slings by one end, with the pocket behind them, and using both hands to throw the staves forward over their heads.

The staff sling has a similar or superior range to the shepherd’s sling, and can be as accurate in practiced hands. It is generally suited for heavier missiles and siege situations as staff slings can achieve very steep trajectories for slinging over obstacles such as castle walls. The staff itself can become a close combat weapon in a melee. The staff sling is able to throw heavy projectiles a much greater distance and at a higher arc than a hand sling. Staff slings were in use well into the age of gunpowder as grenade launchers, and were used in ship-to-ship combat to throw incendiaries.

Medieval staff slingers (stern castle)

Kestros

The kestros (also known as the kestrosphendone, cestrus or cestrosphendone) is a sling weapon mentioned by Livy and Polybius. It seems to have been a heavy dart flung from a leather sling. It was invented in 168 BC and was employed by some of the Macedonian troops of King Perseus in Third Macedonian war.

Siege engines

The traction trebuchet was a siege engine which uses the power of men pulling on ropes or the energy stored in a raised weight to rotate what was, again, a staff sling. It was designed so that, when the throwing arm of the trebuchet had swung forward sufficiently, one end of the sling would automatically become detached and release the projectile. Some trebuchets were small and operated by a very small crew; however, unlike the onager, it was possible to build the trebuchet on a gigantic scale: such giants could hurl enormous rocks at huge ranges. Trebuchets are, in essence, mechanised slings.

Todaya

A Tibetan girl guarding a herd of goats slings a small rock.

Arab shepherd boy using a sling, c. 1900-1920, Jerusalem

Hooded youth rioters using slings

Traditional slinging is still practiced as it always has been in the Balearic Islands, and competitions and leagues are common. In the rest of the world, the sling is primarily a hobby weapon, and a growing number of people make and practice with them. In recent years ‘slingfests’ have been held in Wyoming, USA, in September 2007 and in Staffordshire, England, in June 2008.

According to the Guinness Book of World Records, the current record for the greatest distance achieved in hurling an object from a sling is 437.10 m (1,434 ft 1 in), using a 129.5 cm (51.0 in) long sling and a 52 g (1.8 oz) ovoid stone, set by Larry Bray in Loa, Utah, USA on 21 August 1981. The sling is of interest to athletes who desire to break distance records; the best modern material is a polyester twine (trade name Dacron)[citation needed].

The principles of the sling may find use on a larger scale in the future; proposals exist for tether propulsion of spacecraft, which functionally is an oversized sling to propel a spaceship.

The sling is used today as a weapon primarily by protestors, to launch either stones or incendiary devices, such as Molotov cocktails. Classic woolen slings are still in use in the Middle East by Arab nomads and Bedouins to ward off jackals and hyenas. International Brigades used slings to throw grenades during the Spanish Civil War. Similarly, the Finns made use of sling-launched Molotov cocktails in the Winter War against Soviet tanks. Slings were used during the various Palestinian riots against modern army personnel and riot police. They were also used in the 2008 disturbances in Kenya.[29][30]